It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It was 1942 and we were at war. Radio was at its zenith (no pun intended) but about to get even better. Although I fought the Axis mostly from my crib, Dave Goldin and radio were connected from the beginning.

It wasn't until many years later that I found a copy of the birth announcement that Buddy and Alberta Goldin sent out to proclaim their blessed event. Imagine my surprise to find that the stork pictured on the card was a radio announcer! He is shown interrupting the regular programming of station "B-A-B-Y" with a special bulletin, a new addition to the program schedule! Perhaps my parents had a premonition of the interest that would occupy my thoughts for the next five decades.

According to legend, when I was still very young, my mother took me to the banks of the Harlem River (there being no branch of the Styx nearby, the Harlem made an acceptable substitute). Holding me by one heel, she dipped me into the crystal clear waters in order that I might achieve invulnerability in broadcasting. Unfortunately, I choked on what used to be called an "Orchard Beach Whitefish" and swallowed some of the water flowing past the Bronx. The result was a heavy New York accent that doomed my career in front of a microphone and no doubt preserved the jobs of Don Wilson, Ken Niles and Bill Goodwin.

We all remember our first kiss, our first car, our first radio (don't we?). Mine was an Emerson model #547A which was a cheap plastic set with a satisfying glow in my darkened bedroom. My grandmother had a DeWald model #A501 in her living room that I listened to frequently (Nana would be shocked to know that this radio, made of a very collectible plastic called Catalin, was worth about $750 today!).

One night a week, "Nights In Latin America," hosted by Pru Devon, would come over the Emerson. It was sponsored by Panagra Airlines (which not-too-surprisingly flew to South America) and featured the kind of music favored by guanaco herders on the Argentine pampas and selections played on Bolivian panpipes. I therefore became a world traveler and eventually got to Patagonia in search of the reality behind that show, and to learn what nights in Latin America were really like.

Weekday evenings at 8:00 P.M. was the big show of WQXR's schedule. It was "Symphony Hall" and usually consisted of one or two works of the standard repertory, presented on records. I became a lover of renaissance and classical music. The closest I came to a kid show was "Big Jon and Sparkie" ("No School Today") which I heard over WJZ in New York. Fifty years later, I still have a cocker spaniel named "Sparky IV."

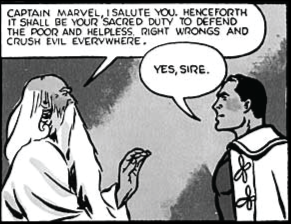

As I grew older and learned to read (or at least look at the pictures), I became seriously influenced by a comic book character. Actually, it was a whole family of characters called "The Marvel Family." In a direct copy of "Superman," Fawcett Publications created Billy Batson, his sister Mary and his "crippled" pal Freddy Freeman, Jr. (there were no handicapped zones back then, if you walked with crutches, you were "crippled"). Given super-human powers by an ancient Egyptian sorcerer (who lived in a subway tunnel!), Billy would utter the sorcerer's name ("Shazam") and turn into Captain Marvel. Over the years, I named two cocker spaniels "Shazam," but no matter how many times I would call them, the lightning bolt changing me into a costumed superhero never arrived (it wasn't a total loss, the spaniels were very affectionate). Your homework is to remember what ancient heroes Shazam's acronymic title represented. Captain Marvel's main appeal for me was the profession of his not-so-secret identity, Billy Batson. Billy worked for a man named Sterling Morris, a portly older gent (he must have been at least 50!), who ran radio station WHIZ in a large city (there is a real station with WHIZ call letters in Zanesville, Ohio, I felt I had to visit this place as soon as I was old enough to drive). Zanesville, home of the world's only "Y" bridge, was a nice place, but Sterling Morris was not on staff at station WHIZ. Billy was known as "the boy newscaster," and that's where my fantasies took me. After all, who wanted to be a crippled newsboy like Freddy Freeman, Jr. when you could read the news on radio! The adventures of Billy Batson, after saying the name of "Shazam" and turning into Captain Marvel, fueled my imagination as to the wonders possible with radio.

As I grew older, I found myself discovering the pleasures to be found collecting 78 rpm records and later radio transcriptions. My friends were discovering girls. I taught myself code (poorly) and became a "ham" operator, WA2BRD and later WB1EZA.

Strangely enough, the first "real" broadcast I ever made was from Radio Moscow! It was in 1957 on a program called "Moscow Mailbag." I mailed a tape of myself talking about tape recording. The show's host played the tape over the Radio Moscow world-wide shortwave service. This was pretty nifty, listening to myself on the 25 meter band over my Zenith Transoceanic (a "portable" set built like an anvil, but weighing more). I suppose my fate as "the man who saved radio" was by now written in stone, but I didn't yet realize it. Let me make clear that "saving radio" refers to collecting the media's programming, and should not be considered in the sense of "salvation" or "rescue of the industry."

My graduation from Stuyvesant High put me in the record business. The event made the front page of the New York Times when a riot broke out in the Greenwich Village theatre where the ceremonies were taking place. I put together a 7-minute documentary (cribbed from local telecasts), cut 45 rpm records at a small studio at 42nd street at 6th Avenue, and mailed a flyer to all the graduating class as listed in the yearbook. I was now in the mail order business too.

With young hormones raging (for radio, there are no steamy sex scenes at this site), I dropped out of NYU for a job at a real station in Alaska. KSEW was a 250 watter on Baronof Island in the southeast panhandle of the state. Alaska had been a state for about three years. Sitka, Alaska was the home of a junior college, a pulp mill, a Coast Guard base, many Alaskan brown bears and not much else. There were no roads in or out, the ferry to Prince Rupert, B.C. ran twice a week and you could fly in only on the daily PB-Y amphibian sea plane (there was no airport). Now this is a setting for small town radio! I was on the air 48 hours a week. I also operated the transmitter, wrote advertising copy (mostly copied from the Sitka Yellow Pages, all 20 of them) and sold time on the station. As a time salesman, I once asked the station manager why we had no cigarette or beer commercials as did most other stations (both were acceptable back then). My boss told me of the time he visited a station rep in New York to ask the same question. The ad executive replied, "When we want to reach a market of 5000 people, we put up a notice in the elevator."

Part of my job at KSEW was an afternoon DJ show for the kids called "Totem Jamboree." Earlier in the day, the station offered programming in the Tlingit language (pronounced "Clink´-it"), as a service to the tribe of Indians who lived on Baronof Island. I came on right afterwards, broadcasting to this huge and receptive audience, sounding like "Radio Free Bronx." However, in all the time I worked there, I never heard a disparaging word about the Harlem River caressing my tonsils. Perhaps my listeners thought we were still transmitting in Tlingit.

Jobs at WVIP in Mt. Kisco, New York and WHBI-FM in Newark, New Jersey taught me more about the realities of small time radio. A short stretch at WOR television taught me I liked radio better. When I got my "first phone ticket," I decided to stay firmly on the other end of the mike and become an operating engineer (Ken Carpenter breathed a sigh of relief). After teaching broadcast electronics at a private school in New York City, I got my big break in network radio. I went to work for the NBC radio network and WNBC-AM/FM in New York and learned about big-time radio. The most important thing I learned (unfortunately too late) was to keep my big mouth shut. During a periodic cutback (which we were told to expect), I was dismissed along with 66 other engineers on the same day. So much for the New York labor market for radio engineers! Finally landing a spot at the Mutual Broadcasting System, I found my NABET card (National Association Of Broadcast Employees and Technicians) from NBC was worthless, so I had to join IATSE (International Alliance Of Theatrical and Stage Employees). When I left Mutual (just about a year before they closed their New York studios) for CBS, I then had to join IBEW local 1212 (International Brotherhood Of Electrical Workers). It seemed one more job and I could play pinochle with my union cards!

While all this was going on in 1968, I started producing records of old radio shows. Starting with a joint project involving the Mutual Broadcasting System, The Longines Symphonette and my small-but-growing archive, my second project was a resounding success. It was called "Themes Like Old Times" and was merely the openings of 90 famous programs segued together. Initially sold to a book club, the record was picked up by a small record label in California and distributed by Dot-Decca. "Themes Like Old Times" eventually rose to #23 on the Variety chart of LP record sales, ahead of the latest Beatles release at one point for several weeks (whatever became of them?). A comedy album of "W.C. Fields and Charlie McCarthy On Radio" that I did for Columbia never rose higher than 198 on the charts, but was nominated for a Grammy award. Not bad for a beginner! Radiola Records, my own label, went on to be nominated for six Grammies, winning the award only once in 1981 ("Best Dramatic and Spoken Word Record"). The next year, they eliminated the category.

My experiences with Columbia, Dot-Decca and others in the record industry led me to the conclusion that this business was filled with knaves and jackals, and so to maintain control over my own product, I began Radiola Records in 1970. It was the first record label devoted to radio broadcasts. "Radio Yesteryear," the parent company, had switched from being a show on a college station to a mom-and-pop mail order company by 1965. We incorporated in 1967 and were the first to offer radio broadcasts for sale. I continued running the company on an absentee basis while I was working in network radio, but finally the economic realities of being my own boss put an end to my network radio career. After 33 years running Radio Yesteryear, I've decided that leaving CBS was financially the right thing to do...but I still miss real radio. Being called "The Man Who Saved Radio" is a big responsibility. The job is daunting and I feel unequal to the task, but it certainly is fun trying to meet the challenge. For example, my good friend Pierre Fermat once told me about a huge collection of transcriptions from the 1920s that he found, but left the directions about where they were kept on a page of his book, saying "I have discovered a marvelous batch of transcriptions which this margin is too narrow to contain." That was the last ever I heard from him!

Can you imagine getting paid to listen to and work with all these great radio recordings? The memories of the famous broadcasts I worked on and the creative, intelligent and talented people I worked with (there were some bastards too) make my radio career a most pleasant part of my life.

Now that I'm retired, what of the future? In addition to continuing to "save radio," I plan to occasionally put down my script and step back from the microphone, say the name of "Shazam," and if that lightning bolt finally strikes, it will be my sacred duty to defend the poor and helpless, right wrongs and crush evil everywhere.

My actual birth announcement as mailed to my Uncle Harvey and others I can’t stand, late in 1942. My father spent the next three years on a battleship in the Pacific, single-handedly sinking the Japanese Navy.

On the air in Alaska. August 1963. Behind me is an example of Tlingit folk art, ahead of me was a better job. Photo by Birt Hilson.

Sept. 1965. Long John Nebel liked me about as much as I liked him, but his was the only all-night show in town where the guests claimed to have been in flying saucers and had the ability to levitate. The photo was taken at NBC Studio 5B (30 Rock Plaza) from where “Monitor” originated on the weekends. The glass behind us is where Radio City tours went by almost continuously, forcing one and all to wear neckties (except Long John).

August 1974. A chance to watch, interview, listen to and have lunch with a radio immortal. You’ll never guess who picked up the check at lunch.

January 1974. Far from the chaos and confusion of network radio, I settled into the peace and tranquility of owning my own company, meeting the payroll and dealing with customers.

February 1998, taken at the CBS net studios on W. 57th Street in New York. The same Ampex 354s were still in use! The Otari deck, the console and the cart machines were new. The IBM tab card reader had been replaced by a slightly more sophisticated computer. It was my first visit in 27 years and only two people actually remembered me. Have I changed that much? Sic transit gloria radio! Photo by Gary Scherer.